I struggle to pinpoint a single answer to this question.

Is problematic dependent on the teacher, the task, or both? Or is one more heavily weighted than the other? I have seen great teachers transform some awful tasks and make them “problematic”…but what do I know? What I do know is that problematic doesn’t have a time-frame, it can last 5 minutes or 5 days.

As the school year cranks up and lesson planning begins, how can we ensure that both teacher and task are embracing the Standards for Mathematical Practice (specifically SMP#1)?

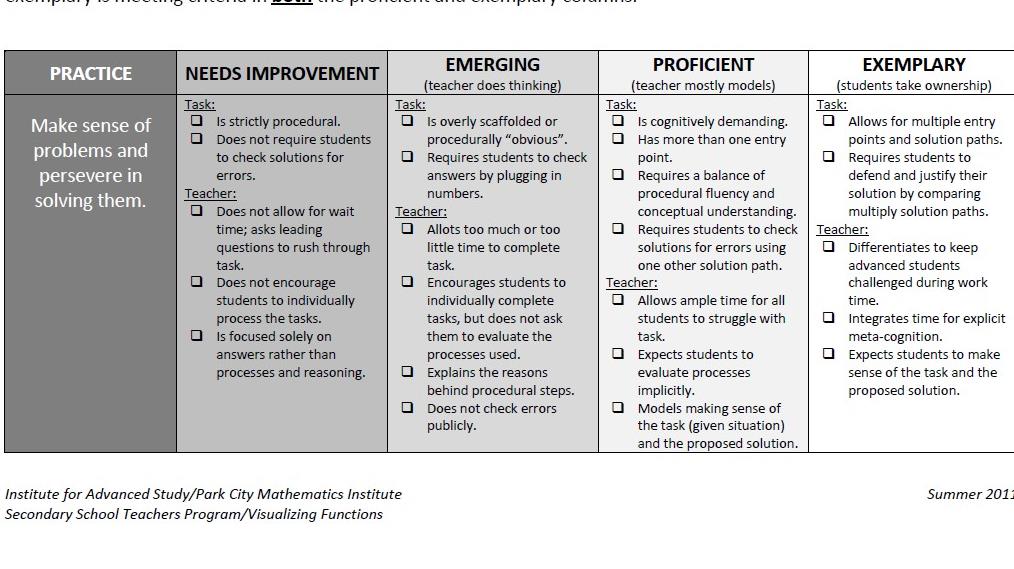

As I try to fine-tune my definition, I found the Institute for Advanced Study/Park City Mathematics Institute SMP Rubric extremely valuable when planning before and reflecting after a lesson.

I have condensed the rubric into 2 pages which I’ve found a little more user friendly when planning. SMP Teacher Growth Rubric V.2

I guess the question I’m asking is, “how can a teacher ensure that the lesson they’re about to teach is problematic?”

Slide #29 is a WINNER! In fact, the whole thing is great. I was even able to find the videos referenced online. Thanks for sharing Ashli. I will definitely be folding this slide and others into future PD sessions.

“Low-floor, high ceiling” or “low-entry, high scalability” has rapidly taken over many of the conversations I have engaged in over the past few months. I love the fact that many of the teachers I work with are using the terms on a regular basis as well.

It’s only a slide deck, but the Five Dimensions of Mathematically Powerful Classrooms outlined in it are an interesting read (perhaps check out slide 29 first) and I think address your last question a bit. Do you use the term “low floor, high ceiling” much in the elementary grades? Check out the slides here: http://map.mathshell.org/conferences/schoenfeld_powerful_classrooms.pdf

And good to see the rubric getting some play. Danielle, Mariam, and Mimi put a lot of work into it that summer and during the next year to revise it 🙂